Introduction

In the previous chapter, we took at look at Fuse's Navigator class and used it to tie our app's views together.

Now that we've got much more of our architecture figured out, it's time to start thinking about how we would interact with a backend. We'll do so by implementing a mock backend, which is a module that will act like a "real" backend, but will just store some data locally in our running app instead of persisting it on the device's storage or in a database somewhere.

Building a mock backend like this isn't strictly necessary when building an app with Fuse. We could just as well pick an existing backend solution, for example, and build our app against that directly. But because this tutorial is meant to be as general as possible, we want to present these concepts in a general, backend-agnostic way so we can focus on the core concepts rather than the details of a specific backend. This will be a good exercise to do at least once so that we can understand what to expect when hooking our app up to a real backend in the future, regardless of which backend solution is actually used.

But before we start building anything, we need to consider what the interface to a typical backend might look like. So let's dive in and take a look!

The final code for this chapter is available here.

Typical backend interface

Backends can be quite complex and how they look/behave can vary a lot, but their most basic interfaces tend to be fairly similar across the board, especially if we're only after a few core features. For example, we can ignore things like initialization, signup, authentication, etc., as those parts will be highly backend-specific, and are features we're not concerned with in our basic app. For our simple app case, we really only need some simple data storage/retrieval and a way to update that data. With these features in mind, a simple backend interface might look something like this:

class MockBackend {

// Returns an array of item objects

getItems() { ... }

// Updates an item

updateItem(...) { ... }

}Then, our app would use this interface in a very straightforward way:

// Get the item objects from the backend

var someItems = MockBackend.getItems();

// Update one of the items in the backend

MockBackend.updateItem(...);This should be straightforward enough. However, we've ignored a very important detail that most (if not all) backends have to deal with: distribution. Our simple interface should work just fine if we already have the data locally, but what if the data is stored on a server somewhere else? We can't have our code just stalling, waiting for the backend server (or disk, etc) to respond with the data we asked for. It could take an indeterminate amount of time for our requests to get to the backend and for the backend to send data back. So, retrieving and updating the data should happen asynchronously. And, in JavaScript, when any asynchronous computations are involved, it's very likely you'll find a Promise or two nearby.

To paraphrase MDN's article about Promises: "A Promise represents a value which may be available now, or in the future, or never." This is a pretty basic explanation of what a Promise can do for us, but already from that description, we can see that this fits our use case of asynchronously communicating with our backend. With Promises, our typical backend interface looks more like this:

class MockBackend {

// Returns a Promise that represents an array of item objects

getItems() { ... }

// Returns a Promise that will be fulfilled when the item is updated in the backend

updateItem(...) { ... }

}From this, it doesn't look like our interface has really changed at all! Of course, actually using these functions (and implementing them in the case of our mock backend) is slightly different, but not by much. For example, the code that uses this interface could look something like this:

// Get the item objects from the backend asynchronously

var someItems = [];

MockBackend.getItems()

.then(items => {

someItems = items;

})

.catch(error => {

console.log("Couldn't get items: " + error);

});

// Update one of the items in the backend asynchronously

MockBackend.updateItem(...)

.catch(error => {

console.log("Couldn't update item: " + error);

})To properly use a Promise, we have to introduce some of our own asynchronous code. The simplest way to interact with a Promise is by calling two of the functions it provides: then and catch.

By calling the then function, we can describe what will happen when the Promise is fulfilled. We do this by passing in another function that optionally accepts the value the Promise is fulfilled with; in this case, the items from the backend. This argument is optional, though. For example, in the case of our updateItem function, the Promise it returns isn't meant to yield a value when the update is complete. We only care about whether or not the Promise was actually completed, so the argument wouldn't be used in this case.

By calling the catch function, we can describe what will happen if an error occured while trying to fulfill the Promise. In this case, we can pass in a function that accepts a description of what caused the failure. For example, a real backend might report an error if it can't connect to the backend server, or authentication failed. Error detection/handling is a complex topic, however, so for the sake of keeping things simple, we're going to skim over a lot of these details. But we'll still want to attach some simple error handlers to our Promises so we have them if we hook up to a real backend later.

There are many more features Promises provide, and they're very useful. But this short description should clarify all we need to know to build and use our mock backend, as well as mock the interfaces of real backends later on.

Note: you can learn more about

Promises in this guide over at MDN, and the A+ promise standard which describes the flavor ofPromises that Fuse conforms to specifically.

All in all, using Promises, we've arrived at a fairly good approximation of what a typical JS-based backend interface will look like, so this is what we'll use to model our mock backend.

Implementing our mock backend

Note: Keep in mind that we'll be moving things around a bit in our project, so we won't be able to compile and/or preview for a while, but we'll be back up and running by the end of the chapter.

Before we start implementing our mock backend, we'll want to talk about how we'll organize our JavaScript moving forward. Currently, we have all of our JavaScript, besides the page models, in the App.js file. As we start adding more functionality of different kinds, it is a good idea to start splitting things up into new classes and to group simlar type of functionality together. In Fuse, as with many other front end systems, we like to separate between models and services. Our models typically model the state of our app, be it which hikes we are displaying or the navigation flow we've defined. The model is however not concerned with talking to backends, interacting with native functionality or other types of services. This is why we usually group these bits of logic in a folder called services, which is functionality that in theory could be useful to any part of our app.

Lets start by creating a folder called Services, which is where we will put our mock backend code. We also create a new JS file called MockBackend.js.

|- MainView.ux

|- App.js

|- Pages

|- ...

|- Services

|- MockBackend.js

...While we're at it, lets also create a Models folder, and move the App.js to it.

|- MainView.ux

|- Models

|- App.js

|- Pages

|- ...

|- Services

|- MockBackend.jsWe also need to make sure we update the path to our model in MainView.ux, since it has now changed place:

<App Model="Models/App">After moving the model class like we just did, you might need to rebuild the project in order for Fuse to pick up the change. This can be done from the menu by going to Preview->Rebuild.

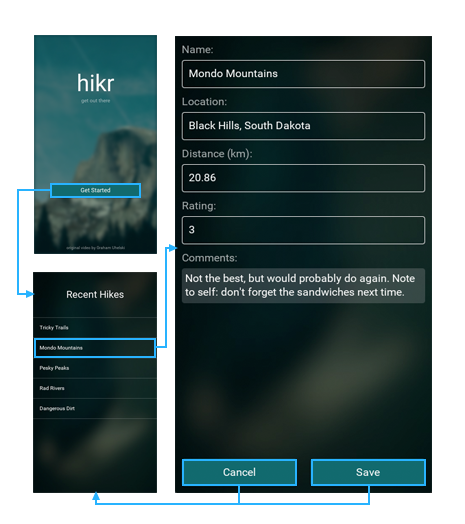

Now we're ready to start implementing our mock backend. As it turns out, our Models/App.js file already contains all the data we'll need to present. Lets start our mock backend implementation by simply moving the hikes array to our newly created Services/MockBackend.js file. But instead of assigning it to this.hikes, lets make it a constant and a part of the files root scope (notice the const hikes part):

const hikes = [

new Hike(

"Tricky Trails",

"Lakebed, Utah",

10.4,

4,

"This hike was nice and hike-like. Glad I didn't bring a bike."

),

new Hike(

"Mondo Mountains",

"Black Hills, South Dakota",

20.86,

3,

"Not the best, but would probably do again. Note to self: don't forget the sandwiches next time."

),

new Hike(

"Pesky Peaks",

"Bergenhagen, Norway",

8.2,

5,

"Short but SO sweet!!"

),

new Hike(

"Rad Rivers",

"Moriyama, Japan",

12.3,

4,

"Took my time with this one. Great view!"

),

new Hike(

"Dangerous Dirt",

"Cactus, Arizona",

19.34,

2,

"Too long, too hot. Also that snakebite wasn't very fun."

)

];A problem we have now, is that the hikes uses the actual Hike model to construct its items. This is a problem, since we don't want our mock backend to know about how we model its data on the client. What we'll do instead is to just use simple JavaScript object literals. We'll also give each item a unique id field, so that we can identiy exactly which item we are working with. This is to cover the case where our backend might have two items with exactly the same data, but that actually represet two unique cases:

const hikes = [

{

id: 0,

name: "Tricky Trails",

location: "Lakebed, Utah",

distance: 10.4,

rating: 4,

comments: "This hike was nice and hike-like. Glad I didn't bring a bike."

},

{

id: 1,

name: "Mondo Mountains",

location: "Black Hills, South Dakota",

distance: 20.86,

rating: 3,

comments: "Not the best, but would probably do again. Note to self: don't forget the sandwiches next time."

},

{

id: 2,

name: "Pesky Peaks",

location: "Bergenhagen, Norway",

distance: 8.2,

rating: 5,

comments: "Short but SO sweet!!"

},

{

id: 3,

name: "Rad Rivers",

location: "Moriyama, Japan",

distance: 12.3,

rating: 4,

comments: "Took my time with this one. Great view!"

},

{

id: 4,

name: "Dangerous Dirt",

location: "Cactus, Arizona",

distance: 19.34,

rating: 2,

comments: "Too long, too hot. Also that snakebite wasn't very fun."

}

];Lets also update our Hike class in Models/App.js to allow us to take care of the new id field:

class Hike {

constructor(id, name, location, distance, rating, comments) {

this.id = id;

this.name = name;

this.location = location;

this.distance = distance;

this.rating = rating;

this.comments = comments;

}

}If you hit save at this point, you might notice the "Problems" tab light up, complaining that it cant resolve the binding to {hikes}. We'll fix this during this chapter.

Our Services/MockBackend.js does not yet export any functionality that would allow our app to access the hikes, so lets get started creating that. We are aiming for the interface we discussed earlier:

export default class MockBackend {

// Returns a Promise that represents an array of hike objects

getHikes() { ... }

// Returns a Promise that will be fulfilled when the hike is updated in the backend

updateHike(...) { ... }

}Start by creating and exporting the MockBackend class:

export default class MockBackend {

}We'll create our getHikes function first.

getHikes() {

}If we wanted this function to return our hikes array, we could simply write something like this (since the hikes array is directly accessible to the MockBackend class, due to being in the same file):

getHikes() {

return hikes;

}But instead, we want the function to return a Promise which will be fulfilled when our hikes are ready. This is to simulate fetching them from a backend. So, our actual getHikes function will look something like this instead:

getHikes() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve(hikes);

});

}Now, instead of returning the hikes array, we create a Promise using new Promise. The Promise constructor takes in a function that will be called in order to fulfill or reject the promise. This function takes in two arguments: resolve, and reject. These arguments are actually functions themselves. resolve is a function that fulfills the Promise we're creating, and if we attached a handler to our Promise using its then function, that handler will be called. In our code, this is all our function needs to call in order to resolve our Promise with our hikes collection. The reject function can be called instead if an error occurs, and any handlers we attached to our Promise via catch will subsequently be called.

We can also use JS' built-in setTimeout function to delay when this will actually be fulfilled by any number of milliseconds. setTimeout also takes two arguments. The first one is a function that will be called sometime in the future, and the second one is a number of milliseconds to delay before calling that function. For example, this code would resolve our Promise after half a second:

getHikes() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(hikes);

}, 500);

});

}This code is very useful if we want to test how our app deals with having to wait for data coming from the backend. However, to keep things simple for ourselves during testing, let's use 0 for the delay instead:

getHikes() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(hikes);

}, 0);

});

}Perfect, now we've got a nice getHikes function with a proper interface and some optional simulated delay!

Now for our updateHike function. This is a function that will take in some information about a specific hike to update in our mock backend, and return a Promise that will be fulfilled when the update has completed. We'll start with an empty function:

updateHike() {

}Then, we'll add some arguments to identify and update a specific hike:

updateHike(id, name, location, distance, rating, comments) {

}In this case, we'll use the id argument to identify the hike we want to update, and the rest of the arguments will be used to overwrite all of the corresponding fields on that hike.

Next, we'll use the Promise constructor and setTimeout just like in getHikes to return a Promise with an optional time delay:

updateHike(id, name, location, distance, rating, comments) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

}, 0);

});

}Looking good! Now, we'll add the code to actually identify the hike by its id and update its members. Lets first filter the array to find the item that matches our id argument, and then update that item by looping over the returned array:

updateHike(id, name, location, distance, rating, comments) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

hikes.filter(hike => {

return hike.id === id

}).forEach(hike => {

//update hike here

});

}, 0);

});

}Once we've identified the hike, we'll update its data with our function's arguments:

updateHike(id, name, location, distance, rating, comments) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

hikes.filter(hike => {

return hike.id === id;

}).forEach(hike => {

hike.name = name;

hike.location = location;

hike.distance = distance;

hike.rating = rating;

hike.comments = comments;

});

}, 0);

});

}Almost done. Finally, we'll make sure we resolve the Promise after the hike object has been updated. Since the Promise we're creating won't return any data, we just call resolve without any parameters, like so:

updateHike(id, name, location, distance, rating, comments) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

hikes.filter(hike => {

return hike.id === id;

}).forEach(hike => {

hike.name = name;

hike.location = location;

hike.distance = distance;

hike.rating = rating;

hike.comments = comments;

});

resolve();

}, 0);

});

}And with that, our mock backend is complete!

Hooking our model up to our mock backend

Now it's time to make sure our model actually gets its data from our newly created mock backend. The first thing we need to do, is to import the mock backend service so that we can use it from our App class:

import MockBackend from 'Services/MockBackend';Next up, we need to actually fetch the hikes array from our backend when we start up our app. We'll do this in the App class constructor. We also remove the "default" hike that is left here from one of the previous chapters:

constructor() {

this.mockBackend = new MockBackend();

this.hikes = [];

this.mockBackend.getHikes().then(hikes => {

this.hikes = hikes;

});

this.pages = [new HomePage()];

}We start by creating a new instance of our mock backend. Notice that we then initialize this.hikes to be an empty array. This is because we do wan't the databinding to resolve initially, since in reality we do not know how long it could take before our backend actually returns the values we ask for.

If we save all our files now, we should see our hikes list reappear. Awesome! This is all we need to do for our HomePage.

Hooking up EditHikePage

We are now ready to hook our EditHikePage up to the mock backend. We need a way to save changes made to a hike, and a way to cancel the edit if we don't want to push it to the backend. Lets switch out the Back button we added in the previous chapter with a Save and a Cancel button instead.

We'll start with the Save button. This button will be almost identical to the Back button we made previously, except that it will also commit the changes made in the editor to our data model in addition to going back to the previous page. So, let's start by simply renaming the existing Back button to Save.

First, in Pages/EditHikePage.ux, we'll change both the text of our button and its clicked handler:

<Text>Comments:</Text>

<TextView Value="{comments}" TextWrapping="Wrap" />

<Button Text="Save" Clicked="{save}" />

</StackPanel>Next, in Pages/EditHikePage.js, we'll add a new function called save:

save() {

//this should save and go back

}This function should save any changes we've made to the current hike to the backend, and also navigate back. One problem now is that since we are in EditHikePage.js we no longer have access to the pages array, which is located in App.js. The easiest way to fix this problem for now is to just pass this array in as an argument when we create the EditHikePage.

goToHike(arg) {

this.pages.push(new EditHikePage(arg.data, this.pages));

}We also have to make sure we make EditHikePage accept and store this new argument:

constructor(hike, pages) {

this.pages = pages;

this.hike = hike;

}Finally, we'll make this button commit any edits we've made in the view. To do this, we'll call mock backends updateHike function, passing in the id and data from our hike object. We now have the same problem as we did with the pages array, so lets pass the mockBackend instance as well as an argument to EditHikePage.

goToHike(arg) {

this.pages.push(new EditHikePage(arg.data, this.pages, this.mockBackend));

}And make sure the EditHikePage constructor takes care of the argument:

constructor(hike, pages, mockBackend) {

this.mockBackend = mockBackend;

this.pages = pages;

this.hike = hike;

}Next up is to actually call the updateHike function of the mock backend, and make sure to print any error messages to our console using the catch method on the returned promise:

save() {

this.mockBackend.updateHike(

this.hike.id,

this.hike.name,

this.hike.location,

this.hike.distance,

this.hike.rating,

this.hike.comments

).catch(err => {

console.log("There was an error updating hike " + this.hike.id + ": " + err);

});

this.pages.pop();

}Great! Now our Save button should be all hooked up. Now, let's implement the Cancel button as well. The Cancel button will be very similar to our Save button, except we'll have to cancel the changes we've made in the editor somehow. But before we worry about that detail, let's go ahead and make our Cancel button, along with a corresponding cancel handler for it.

We'll first add the UX code for the button in Pages/EditHikePage.ux right beneath the code we just wrote for our Save button:

<Button Text="Save" Clicked="{save}" />

<Button Text="Cancel" Clicked="{cancel}" />

</StackPanel>Next, we'll add an empty cancel function and export it in Pages/EditHikePage.js:

cancel() {

}Then, we'll make sure the cancel function will take us back to the previous page by calling this.pages.pop(), just like our save handler:

cancel() {

this.pages.pop();

}Finally, before the handler navigates back to the previous page, we want to revert any changes we've made in the view model. There are a few ways we could do this, but an easy way is to simply store a copy of the hike object that gets passed to the EditHikePage upon creation, and then simply reassign the hike to these values when we want to cancel.

We first need to store a copy of the hike in our constructor. We do this using the ES6 Object.assign function:

constructor(hike, pages, mockBackend) {

...

this.hike = hike;

this.hikeCopy = Object.assign({}, hike);

}Then, in our cancel function, we can use the same function to set the values of the original hike object back to the values of our copy:

cancel() {

Object.assign(this.hike, this.hikeCopy);

this.pages.pop();

}Perfect! Now everything should be hooked up. At this point, we can go ahead and save all of our different files. Once Fuse is finished reloading preview, we finally can try out our fully-functional views!

Our progress so far

Finally, we've got basically all of the major functional pieces of our app in place and hooked up. Now we've got our various pages, models and services working together in perfect harmony and fitted together with a nice, scalable architecture. It looks something like this:

And here's the code for the various files we modified in this chapter:

Services/MockBackend.js:

const hikes = [

{

id: 0,

name: "Tricky Trails",

location: "Lakebed, Utah",

distance: 10.4,

rating: 4,

comments: "This hike was nice and hike-like. Glad I didn't bring a bike."

},

{

id: 1,

name: "Mondo Mountains",

location: "Black Hills, South Dakota",

distance: 20.86,

rating: 3,

comments: "Not the best, but would probably do again. Note to self: don't forget the sandwiches next time."

},

{

id: 2,

name: "Pesky Peaks",

location: "Bergenhagen, Norway",

distance: 8.2,

rating: 5,

comments: "Short but SO sweet!!"

},

{

id: 3,

name: "Rad Rivers",

location: "Moriyama, Japan",

distance: 12.3,

rating: 4,

comments: "Took my time with this one. Great view!"

},

{

id: 4,

name: "Dangerous Dirt",

location: "Cactus, Arizona",

distance: 19.34,

rating: 2,

comments: "Too long, too hot. Also that snakebite wasn't very fun."

}

];

export default class MockBackend {

constructor() {}

getHikes() {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

resolve(hikes);

}, 0);

});

}

updateHike(id, name, location, distance, rating, comments) {

return new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

setTimeout(() => {

hikes.filter(hike => {

return hike.id === id;

}).forEach(hike => {

hike.name = name;

hike.location = location;

hike.distance = distance;

hike.rating = rating;

hike.comments = comments;

});

resolve();

}, 0);

});

}

}Pages/EditHikePage.ux:

<Page ux:Class="EditHikePage">

<ScrollView>

<StackPanel>

<Text>Name:</Text>

<TextBox Value="{hike.name}" />

<Text>Location:</Text>

<TextBox Value="{hike.location}" />

<Text>Distance (km):</Text>

<TextBox Value="{hike.distance}" InputHint="Decimal" />

<Text>Rating:</Text>

<TextBox Value="{hike.rating}" InputHint="Integer" />

<Text>Comments:</Text>

<TextView Value="{hike.comments}" TextWrapping="Wrap" />

<Button Text="Save" Clicked="{save}" />

<Button Text="Cancel" Clicked="{cancel}" />

</StackPanel>

</ScrollView>

</Page>Pages/EditHikePage.js:

export default class EditHikePage {

constructor(hike, pages, mockBackend) {

this.mockBackend = mockBackend;

this.pages = pages;

this.hike = hike;

this.hikeCopy = Object.assign({}, hike);

}

save() {

this.mockBackend.updateHike(

this.hike.id,

this.hike.name,

this.hike.location,

this.hike.distance,

this.hike.rating,

this.hike.comments

).catch(err => {

console.log("There was an error updating hike " + this.hike.id + ": " + err);

});

this.pages.pop();

}

cancel() {

Object.assign(this.hike, this.hikeCopy);

this.pages.pop();

}

}What's next

Now that all of the major parts of our app are in place, it's time to iteratively tweak the look and feel of our app to really make it pop. In the next chapter, we'll build various reusable components with a custom look/feel and sprinkle them all over our app to polish the app and make it look great. So let's get to it!

The final code for this chapter is available here.